More Information

Submitted: December 02, 2025 | Approved: December 09, 2025 | Published: December 10, 2025

How to cite this article: Mehta M, Kadakia A, Mehta H, Gianchandani A. Evaluating a Novel Intranasal Drug Delivery System for Procedural Sedation in Adults Undergoing Endoscopic Procedures – A Prospective, Comparative Study. Int J Clin Anesth Res. 2025; 9(1): 040-046. Available from:

https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.ijcar.1001035

DOI: 10.29328/journal.ijcar.1001035

Copyright License: © 2025 Mehta M, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Intranasal drug delivery; Sedation; Endoscopy; Anesthesia

Evaluating a Novel Intranasal Drug Delivery System for Procedural Sedation in Adults Undergoing Endoscopic Procedures – A Prospective, Comparative Study

Misha Mehta1*, Aditi Kadakia1, Hemant Mehta2 and Ayushi Gianchandani3

1Consultant Anaesthesiologist, Sir H. N. Reliance Foundation Hospital & Research Centre, Mumbai, India

2Chair, Department of Anaesthesia & Pain Management, Sir H. N. Reliance Foundation Hospital & Research Centre, Mumbai, India

3Medicine Student (MBBS/BSc), Imperial College, London, United Kingdom

*Address for Correspondence: Dr. Misha Mehta, Consultant Anaesthesiologist, Sir H. N. Reliance Foundation Hospital & Research Centre, Mumbai, India, Email: [email protected]

Background: Intranasal drug delivery system has several advantages, but evidence associated with their use in patients is limited. This study evaluated the effectiveness of a novel drug delivery system for procedural sedation in adults undergoing endoscopic procedures at a tertiary care Indian centre.

Methodology: A prospective, comparative study was conducted at Sir H.N. Reliance Foundation Hospital & Research Centre (HNRFHRC) in Mumbai (India), including all adult patients posted for gastrointestinal endoscopy between July 2023 and June 2024. Enrolled patients were randomized to receive pre-operative medications by standard protocol (group 1) or intranasally (group 2). The intranasal approach involved attaching the cannula and nozzle of a standard lignocaine nasal spray to a syringe using a 20G needle. All patients were monitored using pulse oximetry, continuous electrocardiography, and noninvasive blood pressure measurements. Standardized assessment tools were used to evaluate the system: Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale (APAIS), functional mobility scale (FMS), visual analogue scale (VAS) for pain, Observer’s Assessment of Alertness and Sedation (OAA/S), and 24-hour postoperative anxiety score (PAS).

Results: Of the 319 patients enrolled (166 control, 153 test), age, gender, and anthropometric characteristics were comparable (p > 0.05). Hemodynamic parameters and oxygen saturation were similar across groups (p > 0.05). The mean APAIS was significantly lower in the test group (p < 0.05), while OAA/S was comparable (p > 0.05). More patients in the test group had a VAS score of zero (92.16% vs. 69.88%, p < 0.05). Higher proportions in the control group had an FMS score of 2 or 3 (7.23% vs. 0%, p < 0.05) and PAS >18 (5.42% vs. 0%, p < 0.05). These findings demonstrate that the intranasal system reduces anxiety and pain and represents a conceptual advance, showing that a simple, low-cost modification can enhance peri-procedural comfort without compromising safety.

Conclusion: The novel intranasal drug delivery system improved pre-operative anxiety, immediate pain control, alertness, and postoperative anxiety. Further studies are warranted.

The utilization of anesthesia support for standard endoscopic procedures has increased over the past few years. Patients undergoing endoscopic procedures generally require opioids and benzodiazepines for sedation. A considerable proportion of individuals undergoing endoscopy exhibit challenges in sedation or have paradoxical agitation in reaction to this combination of drugs. The failure to administer sufficient pain management during gastro-esophagoscopy in individuals may result in hemodynamic instability and esophageal rupture [1]. Hence, the objective of sedation during gastrointestinal endoscopy is to enhance patient tolerance while preserving cardiovascular function and ventilatory status. Intravenous (IV) injection of several medications, including diazepam or midazolam, has been employed to attain conscious sedation during gastrointestinal endoscopy. The challenges associated with tolerance for endoscopy mostly include anxiety and worry over the test results, and pre-medication with midazolam or ketamine is highly successful in inducing anxiolysis. Nevertheless, other authors have documented significant adverse effects (e.g., hypoventilation and hypoxia) and even fatalities associated with the administration of IV sedatives and anxiolytic agents, highlighting the inherent hazards of this method of drug delivery [2]. Therefore, it becomes imperative to look beyond the intravenous route for pre-operative medications.

Intranasal administration of medications has several advantages, including simplicity of delivery, quick onset of action, and patient experience. These qualities may have special importance in therapeutic applications, such as pre-procedural sedation. The nasal cavity demonstrates exceptional appropriateness for drug administration, chiefly owing to the efficacy and high permeability of the nasal mucosa to both small-molecule medicines and biopharmaceuticals [3]. Intranasally given medications employ many channels for central nervous system (CNS) distribution, encompassing intracellular, paracellular, and transcellular methods via the olfactory and trigeminal nerves. Moreover, intranasal administration may circumvent hepatic first-pass metabolism, resulting in enhanced tolerability relative to alternative delivery methods, such as oral or intravenous routes [4].

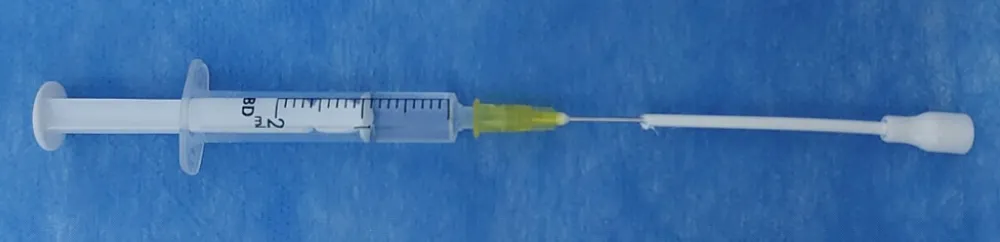

While the current devices used for intranasal drug delivery have several advantages, there are also some limitations that require innovations. These limitations mainly include dosage restriction and barriers to drug permeation, including enzymatic activity in the nasal cavity and ciliary clearance [5,6]. Anatomical variants like ankylosing spondylitis, deviated nasal septum, previously operated cervical spine, and history of nasal surgeries also pose a challenge to intranasal drug administration. To overcome some of these limitations, we have come up with a new model of a nasal drug delivery system with some variations in the method of administration. This model makes use of a cannula in a standard lignocaine intranasal spray, allowing drug delivery directly to the target region for optimal absorption of the drug in the olfactory mucosa. This ultimately leads to rapid uptake of the drugs. In comparison, the standard intranasal mucosal-atomization devices, which are used for nasal irrigation in chronic rhinosinusitis [7], topical nasal anaesthesia before procedures [8], largely allow for optimal distribution in the anterior nasal cavity [9]. Our proposed novel approach involves attaching the cannula and nozzle of a standard lignocaine intranasal spray to a syringe using a 20G needle, allowing anaesthetic drugs to be administered intranasally and accurately and efficiently. In this airless, pressure atomization process, high pressure forces the fluid through a small nozzle as a liquid sheet, leading to fragmentation of the liquid into ligaments and then, ultimately, smaller droplets.

Head-tilt of the patients also plays a key role in the improvement of intranasal drug delivery. Based on published evidence, an administration angle ranging from 300 - 450 may also help in better drug deposition via an intranasal delivery system [10].

The present study was intended to evaluate the effectiveness of the novel drug delivery system for procedural sedation in adults undergoing endoscopic procedures at a tertiary care Indian center. The main aim of the study was to compare the effects of intranasal Ketamine 40 mg with Midazolam 1mg and lignocaine 200 mg, versus conventional intravenous sedation in adult patients undergoing endoscopic procedures under sedation.

A prospective, comparative study was conducted at Sir H.N. Reliance Foundation Hospital & Research Centre (HNRFHRC) in Mumbai (India), including all adult patients posted for gastrointestinal endoscopy procedures, between the period of July 2023 to June 2024. After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval, the patients undergoing the endoscopic procedures and ready for informed consent were enrolled and randomized to receive pre-operative medications by standard protocol (group 1) or receive the medications intranasally with the help of the novel drug delivery system (group 2). The intervention regime is mentioned below in Table 1.

| Table 1: Pre-operative regimen followed in both study groups (IV – Intravenous). | |

| Pre-operative regimen followed in study groups | |

| Pre-operative medications in Group 1 (control) | Pre-operative medications in Group 2 (test group) |

| IV Lignocaine 40 mg + IV Ketamine 20 mg + IV Fentanyl 50 mcg + IV Midazolam 1 mg | Intranasal Ketamine 40 mg + Intranasal Midazolam 1 mg + Intranasal Lignocaine 20 mg, that is 2 puffs (20 minutes before procedure) |

| Both groups received IV propofol as per requirement. | |

Comprehensive demographic and clinical data were gathered. If the endoscopist and anesthesiologist determined that sufficient sedation was not attained, they were given the freedom to administer additional boluses of Propofol. All treatments were executed by proficient gastroenterologists with expertise in performing endoscopic procedures.

Sample size calculation

Based on the pilot study, the mean post-operative OASS scores were 4.72 ± 0.46 and 4.40 ± 0.84, respectively, in the study groups. The sample size was calculated using these values and assuming the following parameters: alpha 0.05, power 0.95. The sample size was calculated using a two-sample t-test. Based on this, the estimated sample size will be 230. The total sample size will be 306, i.e., at least 153 in each group, giving 25% compensation.

Data collection

Data was collected prospectively from adult patients posted for gastrointestinal endoscopy procedures, between the period of July 2023 to June 2024. Clinical parameters, perioperative details, and outcomes were recorded using a standardized data collection form.

Data entry was cross-verified by an independent investigator. Missing or inconsistent entries were rechecked against patient records. Standard definitions and measurement protocols were followed to ensure uniformity.

Outcome assessment

Various standardized outcome assessment scores were used for evaluating the effectiveness of the novel intranasal drug delivery system in the study.

Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale (APAIS): In 1996, the Dutch team led by Moermann created the Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale (APAIS). This questionnaire has six items, making it a cost-effective tool. The items are evaluated using a five-point Likert scale, with the endpoints “not at all” (1) and “extremely” (5) [11] .

In both groups, the APAIS questionnaire was filled out as soon as the patient’s pre-anesthesia check was completed. In the test group, the intranasal drug was administered 20 minutes pre-operatively. After that, patients were wheeled in, and the IV medications were given for the procedure. For the control group, no pre-operative medications were administered, and APAIS was filled directly. The patients were wheeled in & the IV medications were given for the procedure after APAIS in the control group.

Functional Mobility Scale (FMS): This is a standardized scale used to understand the mobility status of patients in clinical studies. The scoring is done from 0 to 5, with 0 indicating full activity, 1 indicating walking with some assistance, 2 indicating walking with assistance for short periods, 3 indicating walking with assistance for activities of daily living/ appointments only, 4 indicating confined to a wheelchair, and 5 indicating bedridden status. The assessment was done one hour after the procedure.

Visual analogue score (VAS): A well-known scoring system to evaluate pain is the Likert scale to understand pain from the patient, with scores between 0 to 10. The patient is asked to score his or her pain subjectively, with 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating maximum pain. The VAS score evaluation was done one hour after the procedure.

Observer’s Assessment of Alertness and Sedation Score (OAA/S score): The OAA/S score is a standardized scoring system used to monitor sedation during procedures and is sensitive to the level of sedation administered. The system includes scoring from 1 to 5, with a score of 5 indicating alertness, 3–4 indicating a moderate level of sedation, and a score of 1–2 indicating unconsciousness [12]. This score was evaluated 1 hour post-procedure.

24-hour Post-operative Anxiety Score (24-hour PAS): The Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) was used to assess the post-operative anxiety status at 24 hours. It is a 40-item self-report assessment of anxiety utilizing a 4-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 to 3 points) for each item. It comprises two dimensions: State anxiety, which refers to one’s current emotional state; and Trait anxiety, which pertains to one’s overall emotional disposition. Each scale comprises 20 components. The state scale has 10 reverse-scored questions, whereas the trait scale consists of 7 [13].

Follow-up data were obtained and documented either through telephonic interviews conducted by the investigator after patient discharge or, in the case of hospitalized patients, during a scheduled in-person follow-up visit.

Hemodynamic parameters

The assessment of hemodynamic parameters (heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure) was conducted pre-operatively, and then at 5 minutes, 10 minutes, and 30 minutes during surgery. The same frequency of oxygen saturation was also noted in both study groups.

Statistical analysis

The data was entered in a Microsoft Excel sheet by a blinded physician from the study team. The normality of the data was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Continuous variables were expressed as mean & standard deviation, and categorical data will be expressed as numbers and percentages. Depending upon the data, differences between the control group and the test group were compared using an independent t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were compared using the 𝜒2 test. A two-tailed p - value of <0.05 for all analyses was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 17 (StataCorp. 2021. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC).

A total of 319 patients were enrolled in the study, 166 in the control group and 153 patients in the test group. The mean age was comparable between groups (p > 0.05), with a median age being 47 years in both study groups. The gender distribution was comparable between groups, with a nearly equal distribution of males and females in both groups. Anthropometric parameters were also statistically comparable (p > 0.05). Most patients in both groups belong to the ASA grade 2 class. Complete demographic and baseline details are given in Table 2.

| : Comparison between mean values of study groups by unpaired t test, comparison of gender distribution, and ASA grade by Chi-square test. p < 0.05 considered significant (BMI – Body Mass Index). | |||

| <Demographic and baseline characteristics in study groups (n = 319) | |||

| Parameter assessed | Control Group (n = 166) | Test group (n = 153) | p value |

| Age details | |||

| Mean age (years) | 49.53 + 16.04 | 48.51 + 16.15 | >0.05 |

| Median age with range (years) | 47 (15 - 85) | 47 (19-86) | - |

| Gender distribution | |||

| Number of males (%) | 82 (49.4%) | 75 (49.02%) | >0.05 |

| Number of females (%) | 84 (50.6%) | 78 (50.98%) | |

| Anthropometric details | |||

| Mean height (cm) | 160.60 + 8.99 | 160.68 + 7.22 | >0.05 |

| Mean weight (kg) | 68.04 + 14.74 | 66.91 + 11.93 | >0.05 |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) | 26.37 + 5.46 | 25.89 + 4.22 | >0.05 |

| ASA grade | |||

| Grade 1 | 66 (39.79%) | 66 (43.13%) | >0.05 |

| Grade 2 | 100 (60.21%) | 87 (56.87%) | |

Comparison of hemodynamic parameters and oxygen saturation in study groups

The hemodynamic parameters, as well as the oxygen saturation, were noted to be statistically comparable between the test and the control groups at all time points of assessment (p > 0.05) (Table 3).

| Table 3: Comparison between mean values of hemodynamic parameters by Unpaired t-test. p < 0.05 considered significant. | |||

| Hemodynamic parameters in study groups (n = 319) | |||

| Parameter assessed | Control Group (n = 166) | Test group (n = 153) | P value |

| Heart rate | |||

| Pre-operative | 75.11 + 10.98 | 75.59 + 10.14 | >0.05 |

| 5 min | 74.36 + 10.29 | 75.02 + 9.90 | >0.05 |

| 10 min | 74.10 + 10.42 | 74.06 + 10.89 | >0.05 |

| 30 min | 74.03 + 9.15 | 73.44 + 9.34 | >0.05 |

| Systolic blood pressure (SBP) | |||

| Pre-operative | 126.66 + 20.90 | 128.20 + 18.22 | >0.05 |

| 5 min | 122.44 + 15.29 | 120.67 + 13.65 | >0.05 |

| 10 min | 119.45 + 15.27 | 117.84 + 12.11 | >0.05 |

| 30 min | 120.81 + 13.07 | 119.41 + 10.58 | >0.05 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (DBP) | |||

| Pre-operative | 74.01 + 7.89 | 74.13 + 9.13 | >0.05 |

| 5 min | 70.64 + 8.26 | 72.09 + 9.00 | >0.05 |

| 10 min | 69.81 + 7.71 | 70.97 + 9.21 | >0.05 |

| 30 min | 71.21 + 7.35 | 71.19 + 7.23 | >0.05 |

| Oxygen saturation | |||

| Pre-operative | 99.87 + 0.47 | 99.95 + 0.28 | >0.05 |

| 5 min | 99.76 + 0.54 | 99.82 + 0.40 | >0.05 |

| 10 min | 99.78 + 0.49 | 99.82 + 0.42 | >0.05 |

| 30 min | 99.84 + 0.40 | 99.89 + 0.34 | >0.05 |

APAIS, VAS for pain, and OAA/S score in study groups

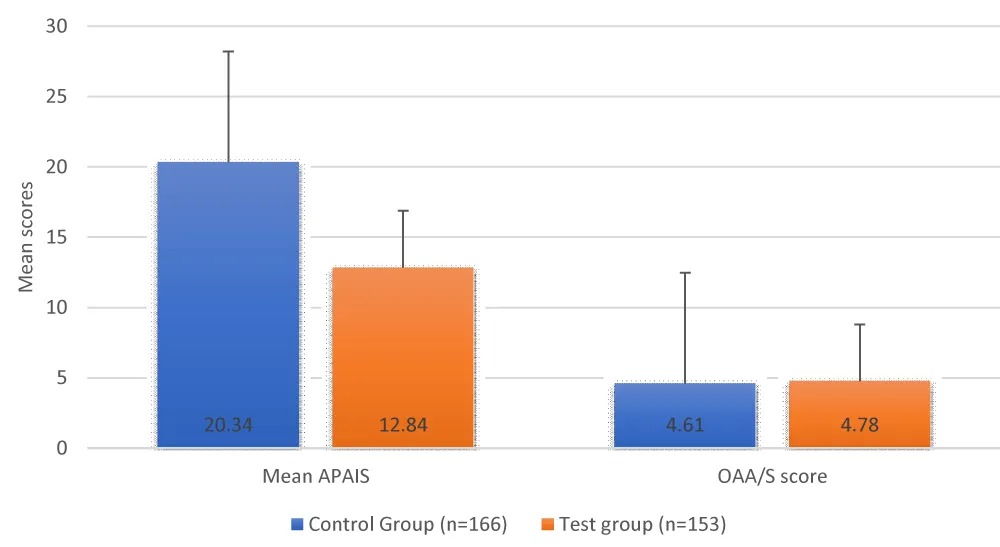

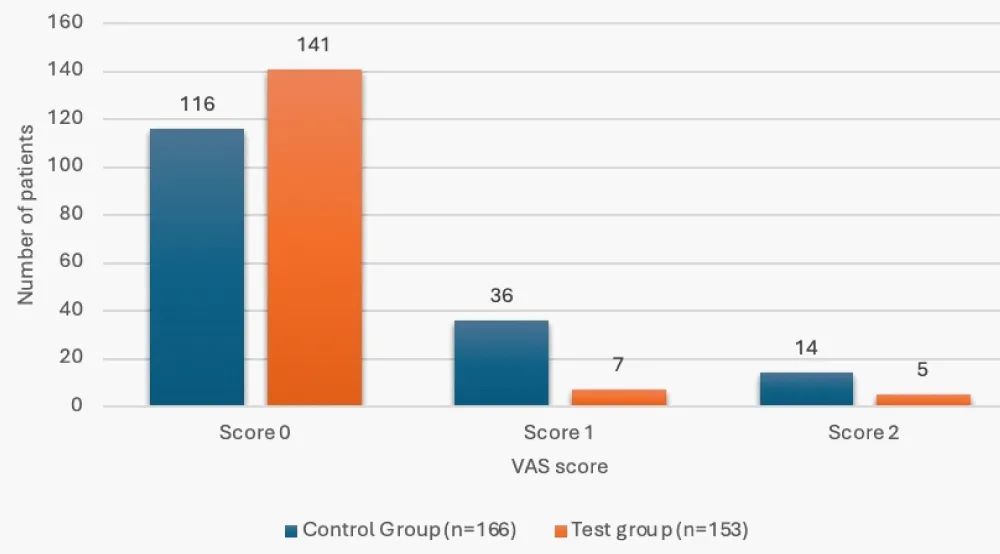

The mean APAIS was all noted to be significantly lower in the test group (p < 0.05), while the OAA/S score was statistically comparable between the study group (p > 0.05). Significantly greater number of patients in the test group had a VAS score of zero versus the control group (92.16% vs. 69.88%) (Table 4, Figures 1,2).

| Table 4: Comparison between mean values of both groups by Unpaired t test, VAS score status comparison done by Chi-square test. p < 0.05 considered significant. | |||

| Comparison of APAIS, VAS pain score, and OAA/S score between study groups (n = 319) | |||

| Parameter assessed | Control Group (n = 166) | Test group (n = 153) | p value |

| Mean APAIS | 20.34 + 6.75 | 12.84 + 4.76 | <0.05 |

| OAA/S score | 4.61 + 0.63 | 4.78 + 0.64 | >0.05 |

| VAS score comparison | |||

| Score 0 | 116 (69.88%) | 141 (92.16%) | <0.001 |

| Score 1 | 36 (21.69%) | 7 (4.58%) | |

| Score 2 | 14 (8.43%) | 5 (3.27% | |

Figure 1: Comparison of mean APAIS and OAA/S scores between study groups.

Figure 2: VAS score status in the study groups.

Status of FMS and 24-hour PAS score in the study

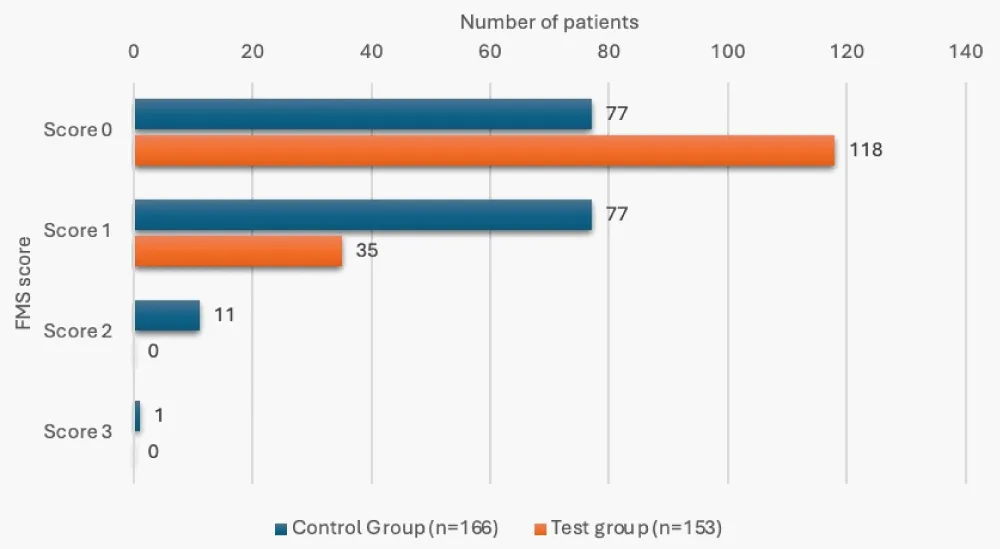

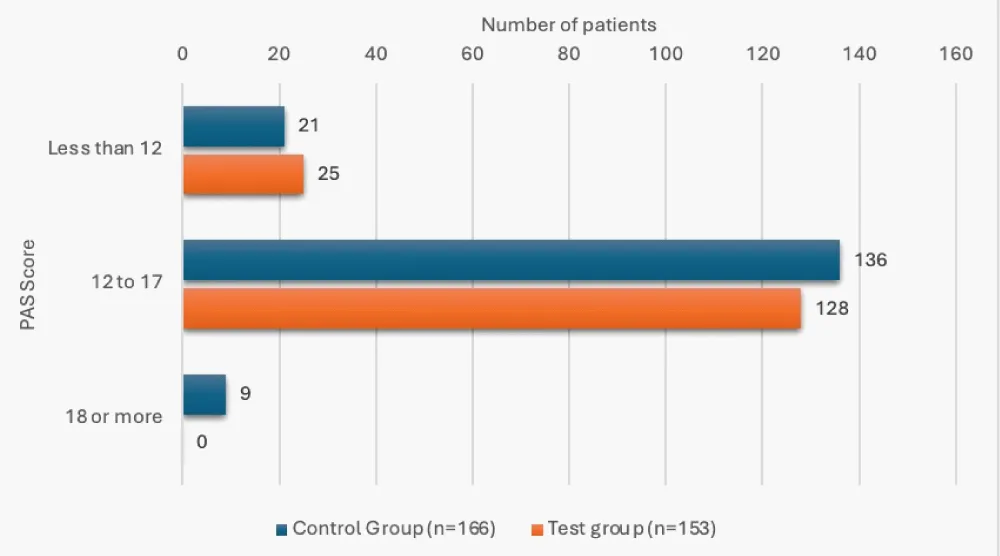

12 of the patients in the control group (7.23%), while none in the test group, had an FMS score of 2 or 3, and this was a significant finding (p < 0.05). 9 patients in the control group (5.42%) had a 24-hour-PAS score of 18 or more, versus none in the test group, and this difference was significant (p < 0.05) (Table 5, Figures 3,4). The mean 24-hour PAS score was noted to be significantly higher in the control group versus the test group (12.83 + 2.29 vs. 12.20 + 1.28, p < 0.05, considered significant by unpaired t-test).

| Table 5: Comparison of FMS and 24-hour PAS between groups done by Chi-square test, p < 0.05 considered significant. | |||

| Comparison of FMS and 24-hour PAS status between study groups (n = 319) | |||

| Parameter assessed | Control Group (n = 166) | Test group (n = 153) | p value |

| FMS score | |||

| 0 | 77 (46.39%) | 118 (77.12%) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 77 (46.39%) | 35 (22.88%) | |

| 2 | 11 (6.63%) | 0 | |

| 3 | 1 (0.60%) | 0 | |

| 24-hour-PAS score | |||

| Less than 12 | 21 (12.65%) | 25 (16.34%) | 0.01 |

| 12-17 | 136 (81.93%) | 128 (83.66%) | |

| 18 or more | 9 (5.42%) | 0 | |

Figure 3: FMS score status in study groups.

Figure 4: 24 hour PAS score status in study groups.

Intranasal administration of medications for procedural sedation has demonstrated a rapid and consistent onset of sedation, along with a predictable plasma concentration profile in young, healthy adults and children [14,15]. The treatment of elderly individuals may benefit from this method as well, since it facilitates easier titration of medications. The intranasal route would also help in the alleviation of pre-operative anxiety, as was evident in our study as well. The pre-operative APAIS was significantly lower in the intranasal group, indicating lower anxiety versus the intravenous control group. Despite these advantages, there are some barriers related to the intranasal devices, hampering drug permeation and fast uptake of the medications. Our novel approach leveraged an airless, pressure atomization process, with high pressure forcing the fluid through a small nozzle as a liquid sheet, leading to fragmentation of the liquid into smaller droplets (Figure 5). Intranasal drug delivery, particularly for anaesthetic drugs like midazolam and ketamine, presents challenges in monitoring the quantity of drug administered and the location of delivery and absorption. While lignocaine intranasal sprays utilize air atomization, this method lacks precision in drug delivery monitoring. Additionally, through this process, more than one drug cannot be administered together, and the quantity of drug administered cannot be monitored with complete effectiveness. Therefore, we proposed the idea of attaching a syringe to a standard spray cannula and nozzle.

Figure 5: Syringe attached to a standard spray cannula and nozzle for intranasal drug administration in study.

The atomization process in intranasal drug delivery relies on fluid pressure or atomization pressure as its energy source. Atomization pressure refers to the force per unit area in an atomization orifice that is required to transform the liquid into fine particles [16]. Therefore, to achieve optimal distribution of anaesthetic drugs through intranasal sprays, maximizing pressure and force while minimizing the diameter of the atomization orifice, or the nozzle, is crucial. In our model, the nozzle diameter is much smaller compared to the cannula diameter, which generates smaller droplets for effective drug distribution.

Optimization of intranasal sedative drug delivery necessitates careful consideration of the nasal cavity’s anatomical and physiological characteristics. The nasal apparatus serves multiple physiological functions, including thermal regulation and humidification of inspired air, filtration of particulate matter, and olfactory sensation. Most types of nasal mucosa are involved in drug absorption, but the respiratory and olfactory mucosa collectively constitute the central portion of the nasal cavity and are of primary relevance for intranasal drug administration due to their delivery pathways. The respiratory mucosa, encompassing the lateral walls and turbinates, and lined by a ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium with 300 microvilli per cell, is the target side for many standard intranasal drug administration methods [17]. It is the predominant area (approximately 130 cm2) and exhibits the highest degree of vascularization within the nasal cavity, along with a large surface area due to microvilli-covered epithelium, making it an optimal site for systemic drug absorption following nasal administration [18]. In contrast, the olfactory mucosa comprises a relatively minor fraction (≤10%) of the total nasal cavity surface area, spanning 2 - 12.5 cm2 [19,20]. It is made of ciliated chemosensory pseudostratified columnar epithelium and is situated on the superior-most aspect of the cavity, which often presents a challenge for drug deposition via nasal administration routes for most drug delivery devices. Direct CNS delivery of drugs via the respiratory mucosa is limited to the trigeminal nerve pathway, while the olfactory mucosa is a unique anatomical interface where the central nervous system directly contacts the external environment [21]. Furthermore, the presence of arteries running alongside olfactory axon bundles, which supply nutrients to OSNs, introduces an additional transport mechanism. Drug substances are likely propelled by the perivascular pump, driven by systolic-associated high-pressure waves through arterioles. This mechanism enables rapid transport directly to the brain, with substances reaching the CNS via the olfactory pathway in approximately 0.33 hours, and via the trigeminal pathway in 1.7 hours [22]. Our model makes use of a cannula in a standard lignocaine intranasal spray, which allows for drugs to be delivered directly to the target region for optimal absorption of the drug in the olfactory mucosa to allow for rapid uptake of the drugs. In comparison, the standard intranasal mucosal atomization devices, which are used for nasal irrigation in chronic rhinosinusitis [7], rescue therapies for seizure clusters [20], and topical nasal anaesthesia before procedures [8], largely allow for optimal distribution in the anterior nasal cavity [9]. Hence, the drugs administered intranasally in our study would have been absorbed through the highly vascularized nasal mucosa directly into the systemic circulation, thus bypassing first-pass hepatic metabolism and resulting in a faster peak plasma concentration and a higher bioavailability.

Studies show that the tilted head back orientation is optimal for drug delivery to the posterior respiratory and olfactory mucosa sites, while a forward head tilt is better for anterior deposition of the drugs for a local anesthetic effect. It allows for drug deposition in these areas, prevents the spray from dripping forward before it is atomized, and allows for complete atomization of the spray within the nasal passage by administering it deep in the nasal cavity [10]. Administration angle is also an important factor to consider when trying to optimize the deposition and absorption of an intranasal drug. Additionally, it has also been reported that drug advancement through the nasal valve and deposition in the nasal mucosa is also improved at an administration angle less than 45° [10]. Therefore, a lower administration angle ranging from 30° to 45° was considered in our study, optimal for maximizing drug deposition.

In our study, this novel intranasal system led to better pain control, greater mobility, and lower post-operative anxiety versus the intravenous group. These findings can be explained by better cooperation with the patient and the lack of any post-procedural adverse events. Additionally, the hemodynamic parameters and alertness during surgery were comparable between the intranasal and the intravenous study groups. These findings clearly indicate an advantage of our novel intranasal system in terms of delivering effective procedural sedation, without jeopardising hemodynamic variables.

The study had many noteworthy strengths and limitations. The preparations used in the study were the same for all patients in the respective study group, to avoid any inter-patient pharmacokinetic variability. The sample size was also adequate to conclude. Nevertheless, a limitation of the study was that it was conducted at only one hospital; hence, the overgeneralization of the findings to the Indian population should be done with caution.

The assessed novel intranasal drug delivery system was successful in achieving significantly better pain control, mobility, and lowering post-operative anxiety versus the intravenous procedural sedation group, without hemodynamic alterations. This is the first study from India to evaluate the novel intranasal drug delivery system with success, and future studies with a larger sample and a multi-centre study design can help in validating our study findings.

The authors declare that there were no additional contributors who met the criteria for acknowledgement beyond the listed authors, and no collaborating bodies required acknowledgment.

No financial grants or external funding were received for this study.

- Borrat X, Valencia JF, Magrans R, Gimenez-Mila M, Mellado R, Sendino O, et al. Sedation-analgesia with propofol and remifentanil: concentrations required to avoid gag reflex in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Anesth Analg. 2015;121(1):90-96. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0000000000000756

- Zuccaro G Jr. Sedation and sedationless endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2000;10(1):1-20, v. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10618451/

- Gänger S, Schind K. Tailoring formulations for intranasal nose-to-brain delivery: a review on architecture, physico-chemical characteristics and mucociliary clearance of the nasal olfactory mucosa. Pharmaceutics. 2018;10(3):116. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics10030116

- Keller LA, Merkel O, Popp A. Intranasal drug delivery: opportunities and toxicologic challenges during drug development. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2022;12(4):735-757. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13346-020-00891-5

- Huang Q, Chen X, Yu S, Gong G, Shu H. Research progress in brain-targeted nasal drug delivery. Front Aging Neurosci. 2024;15:1341295. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2023.1341295

- Khatri DK, Preeti K, Tonape S, Bhattacharjee S, Patel M, Shah S, et al. Nanotechnological advances for nose-to-brain delivery of therapeutics to improve Parkinson's therapy. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2023;21(3):493-516. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159x20666220507022701

- Manji J, Singh G, Okpaleke C, Dadgostar A, Al-Asousi F, Amanian A, et al. Safety of long-term intranasal budesonide delivered via the mucosal atomization device for chronic rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2017;7(5):488-493. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.21910

- Fuehner T, Fuge J, Jungen M, Buck A, Suhling H, Welte T, et al. Topical nasal anesthesia in flexible bronchoscopy--a cross-over comparison between two devices. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0150905. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150905

- Varricchio A, Brunese F, La Mantia I, Ascione E, Ciprandi G. Choosing nasal devices: a dilemma in clinical practice. Acta Biomed. 2023;94(1):e2023034. Available from: https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v94i1.13738

- Kundoor V, Dalby RN. Effect of formulation- and administration-related variables on deposition pattern of nasal spray pumps evaluated using a nasal cast. Pharm Res. 2011;28(8):1895-904. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-011-0417-6

- Moerman N, van Dam FS, Muller MJ, Oosting H. The Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale (APAIS). Anesth Analg. 1996;82(3):445-51. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/00000539-199603000-00002

- Bagchi D, Mandal MC, Das S, Basu SR, Sarkar S, Das J. Bispectral index score and observer's assessment of awareness/sedation score may manifest divergence during onset of sedation: study with midazolam and propofol. Indian J Anaesth. 2013;57(4):351-7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5049.118557

- Spielberger CD. State-trait anxiety inventory. In: Weiner IB, Craighead WE, editors. The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology. 2010. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0943

- Knoester PD, Jonker DM, Van Der Hoeven RT, Vermeij TA, Edelbroek PM, Brekelmans GJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of midazolam administered as a concentrated intranasal spray: a study in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;53(5):501-7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.01588.x

- Musani IE, Chandan NV. A comparison of the sedative effect of oral versus nasal midazolam combined with nitrous oxide in uncooperative children. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2015;16(5):417-24. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40368-015-0187-7

- Mohandas A, Luo H, Ramakrishna S. An overview on atomization and its drug delivery and biomedical applications. Applied Sciences. 2021;11(11):5173. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/app11115173

- Bourganis V, Kammona O, Alexopoulos A, Kiparissides C. Recent advances in carrier-mediated nose-to-brain delivery of pharmaceutics. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2018;128:337-62. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpb.2018.05.009

- Erdő F, Bors LA, Farkas D, Bajza Á, Gizurarson S. Evaluation of intranasal delivery route of drug administration for brain targeting. Brain Res Bull. 2018;143:155-70. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2018.10.009

- Gizurarson S. Anatomical and histological factors affecting intranasal drug and vaccine delivery. Curr Drug Deliv. 2012;9(6):566-82. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2174/156720112803529828

- Chung S, Peters JM, Detyniecki K, Tatum W, Rabinowicz AL, Carrazana E. The nose has it: opportunities and challenges for intranasal drug administration for neurologic conditions, including seizure clusters. Epilepsy Behav Rep. 2022;21:100581. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebr.2022.100581

- Crowe TP, Greenlee MHW, Kanthasamy AG, Hsu WH. Mechanism of intranasal drug delivery directly to the brain. Life Sci. 2018;195:44-52. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2017.12.025

- Lochhead JJ, Thorne RG. Intranasal delivery of biologics to the central nervous system. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64(7):614-28. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2011.11.002