More Information

Submitted: February 17, 2025 | Approved: February 25, 2025 | Published: February 26, 2025

How to cite this article: Ernacio SM, Rodriguez MPL. Minimising Carbon Footprint in Anaesthesia Practice. Int J Clin Anesth Res. 2025; 9(1): 001-009. Available from:

https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.ijcar.1001026

DOI: 10.29328/journal.ijcar.1001026

Copyright License: © 2025 Ernacio SM, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Anesthesia; Residency training; Research

Experience of Anesthesiology Residents in the conduct of their Research during Residency Training at Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center

Shein Melicer Ernacio* and Maria Pura L Rodriguez

Brgy Sabang, Danao City, Cebu, Philippines

*Address for Correspondence: Shein Melicer Ernacio, Medical Officer III, Brgy Sabang, Danao City, Cebu, Philippines, Email: [email protected]

Introduction: Research provides a framework for Anesthesia residents who are critical thinkers who approach clinical practice with an open mind. The goal of this study was to determine current attitudes regarding performing research during residency as well as perceived obstacles to doing so. A resident physician should be ready to face the challenges of the growing technology, tons of journals published in different portals, and increasing sophistication of the health care delivery system. Practice-based learning, systems-based practices, and medical knowledge are the vital core directly affected by strong research skill set.

Methods: The study was done through a survey of all 15 current residents in Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center Anesthesia Resident. They answered a 13 self-administered survey, which was adopted from previous similar research. Data was collected for 1 week to give time to the busy schedule of the resident.

Results: Respondents cited that the lack of time in balancing clinical and research responsibilities is the most common obstacle encountered by 86.7% of respondents. Researchers feel they have inadequate research skills and a lack of time in balancing responsibilities between family and work was among the most common answers by the respondents. 2nd prevalent barrier to research during residency was a lack of mentoring.

Conclusion: The top barriers to research are lack of time and inadequate access to research mentors. These barriers can be addressed to optimize the current research environment for residents. Anesthesia residents identified several critical aspects that they believe are obstacles to research. These findings can be used by programs to overcome hurdles and increase the inclusion of research into residency training.

Background of the study

Research papers and activities are an integral fragment of residency training, they have become a critical piece for the future of modern residency training. A resident physician should be ready to face the challenges of the growing technology, tons of journals published in different portals, and increasing sophistication of the health care delivery system. Practice-based learning, systems-based practices, and medical knowledge are the vital core directly affected by a strong research skill set. Thus being involved in research, promotes critical thinking, helps in identifying clinical gaps, as well as promotes continuous learning. Research promotes critical understanding, and incorporates scientific evidence related to patients’ health problems and treatment into clinical practice.

Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center gives special importance to Research and evidence-based programming, as stated in the quality policy of the hospital [1]. It has been a requirement to finish a research paper before graduating from residency in all specialty training in the hospitals. However, research presentations or publications outside the hospital are not that common. Understanding the factors and experiences of the recent graduates and current residents of the Anesthesia Residency training may improve research quality in the department. Even with the requirement to finish the research before graduating from residency, there are fewer activities to help the residents in achieving this.

In this age of evidence-based medicine, conducting research has become more and more relevant for residents in training. Experience in research allows trainees to develop their critical thinking skills, and mastery of their research subject, and enhance their understanding of medical literature. Completed research can also be used as evidence data for further improving patient care and their outcome. However, the completion of residency training alone is a complicated task to accomplish, much more in balancing residency with research.

In one research paper done in Singapore where the interest and experience of Anesthesiology Residents in doing research were reviewed, it was found that there is a low rate of research participation of less than 35% even though research is required to complete training. 71% of residents participating in research, only do so for it is required in their residency training. And less than 50% of them are interested in even participating in research activities. This may be because 48% of the respondents had no previous training in research [2].

Recognizing barriers to completing a residency research project is the first step to improving program-specific solutions. Lack of dedicated time available to perform research, lack of department research manpower support, and lack of mentorship are the top 3 identified barriers to research completion [3]. Planning may contribute to the successful completion of a research project within residency years. Once the research process is underway, solicitation of feedback throughout the year is essential. Review of abstracts and manuscripts is likely to increase acceptance rates for publication and journal presentation [4]. A dedicated academic rotation that includes protected time, senior faculty mentorship, and program funding, can lead to productive research in residents. Support of academic work during residency training may encourage engagement in a variety of academically oriented activities. In a residency training where a residency research program was implemented, there was a noted increase of almost 20% after a year of implantation [5]. And in the US anesthesiology teaching departments have become more aware of the need to include research into the residency curriculum. They cited that outcomes of resident investigations will be “suitable for presentation at local, regional, or national scientific meetings and that many will result in peer-reviewed abstracts or manuscripts”. Therefore, an important mission of a residency is to educate its residents to appreciate the necessary work, skill set, and time expended by clinician-researchers to do academic work and to teach critical evaluation of the scientific literature [6].

An anesthesia training program in Canada had substantial gains in building its research program. Fostering a culture of research within the hospital. Their training program was able to publish numerous research in acute and chronic pain. They continue to run numerous clinical pain studies [7]. In their training program manual, activities like research mentorship, research days, research dinners, and other scholarly activities give priority to research. They have a research coordinator within their training program, something the Anesthesia Department has recently established.

Significance of the study

An assessment of the interest, obstacles, and experience of Anesthesia residents in terms of Research participation is essential in this era of evidence-based medicine. The very importance of this research is to identify gaps in research policy within the department and help the department in nurturing the resident’s research interests and skills. Identifying the obstacle and existing assistance in terms of research participants will be an eye-opener for the department policy-making body in formulating activities and programs that prioritize the research participation of residents.

Objectives of the study

The general objective of the study is to investigate the experience of Anesthesiology Residents in conducting Research during Residency Training in VSMMC

The specific objectives of the study are as follows:

- 1. To determine the demographic profile of each Anesthesia Resident in VSMMC

- Gender

- Age

- Marital or Perinatal

- Current year

- Highest degree

- 2. To determine the research profile of each Anesthesia Resident in VSMMC

- Reason for taking up research

- Area of research interest

- Previous research activities

- Previous research training

- To determine the obstacle in the conduct of research for Anesthesia residents in VSMMC

- To determine the activities or assistance that may encourage involvement in Research activities for Anesthesia residents in VSMMC

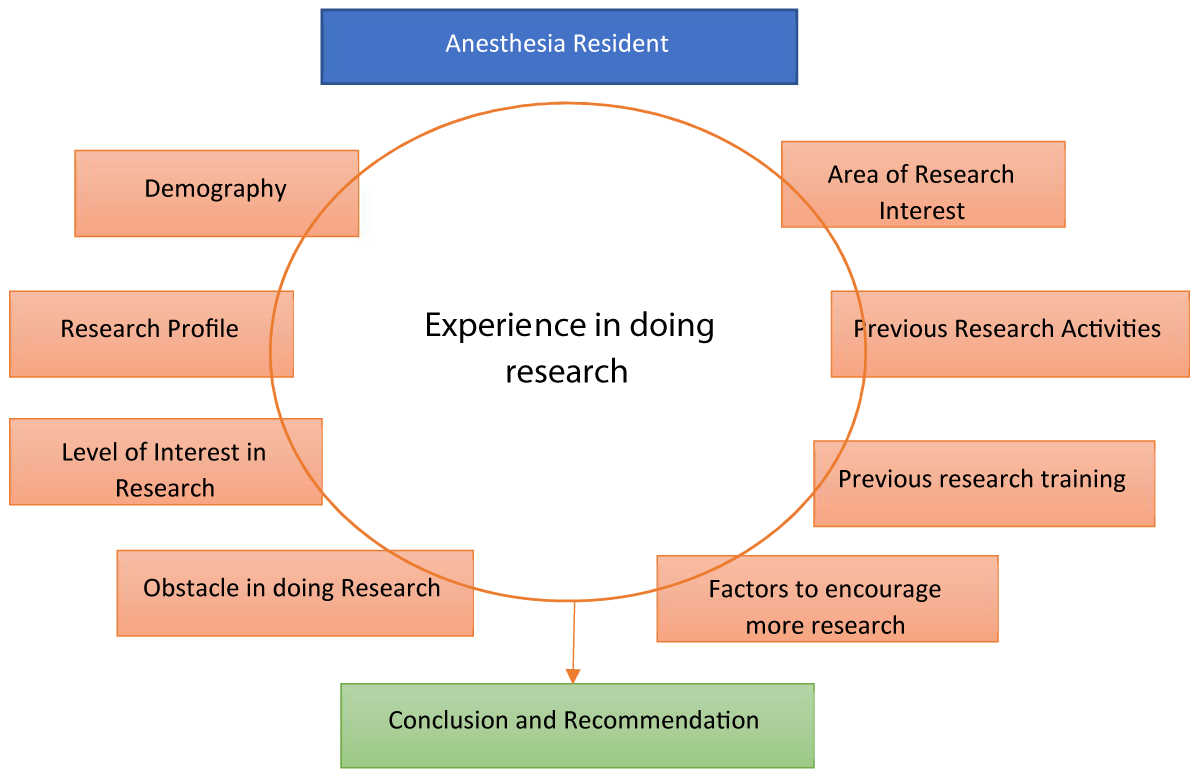

Conceptual framework

Figure 1 shows the factors influencing the experience in doing research for an Anesthesia resident. The framework was inspired by different factors in other research.

Figure 1: Conceptual Framework of research experience of Anesthesia residents (inspired by figure 2 of reference [16]).

Despite the clear emphasis on residency training to be involved in research, most trainees find it difficult to finish their research paper during their residency training. Residency rotation dedicated to research time is not part of the job description for a senior resident in some parts of the world. Only 22% of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery residents in France were able to finish their papers during working training hours. An international study surveying the barriers faced by a residency in completing their research in 5 different continents (America, Europe, Asia, Oceania, and Africa) showed that institutional factors like “lack of research project conducted in the department” have more impact. Individual factors such as “lack of personal interest” and lack of interest in conducting research projects” were the least important limiting factors. Individual factors are hardest to overcome compared to institutional factors. The paper also showed that limited dedicated time for the conduct of research was the most considerable barrier to conducting research projects. The result of the paper showed that residents in training understand the value of completing a research project [5].

Another paper with the same framework of study with the same framework. The research showed that 13 academic centers for Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery in Canada, identified “lack of time”, “insufficient access to research supervisors and mentors”, and “the research ethics process” were among the perceived barriers by a resident in conducting research. It showed that most of the residents in Canada do not have protected research and their respective institutions do not allow time off for research. The same paper identified in their survey a potential solution for improving the conduct of research. Among the solutions identified were protected time and mandatory research half days included in the curriculum. The lack of research mentors and supervisors was the second most identified barrier perceived by the resident. Having a mentor to inspire and support the resident is part of the important process. One of the identified barriers identified in residency training in Canada was the research ethic process. The survey showed that residents lost momentum and significant research delay while waiting for the results from the research ethics board reviews. The importance of the ethics review is not deniable, but streamlining and simplifying the approval process may facilitate increased research output [2].

A General Surgery Residency training at the University of Connecticut implemented a new integrated research program in their curriculum. This was then evaluated after 2 years, and it compared the number of publications as well as abstract presentations in regional, national, and international meetings. The evaluation showed a 3 fold increase in podium and poster presentation by their trainees. As well as a significant increase in the national and international podium presentations. Significantly higher trainees who followed the 2-year research track had more publications. Their research program had 7 key elements, which were: research curriculum, annual research day, research mentors, research project repository, statistical support, research director/coordinator, and database mining. For their Research curriculum, they identified that it was imperative to establish a research curriculum that could provide their residents with the basic tools to perform research. They did this by conducting monthly meetings and lectures by the institutional review board staff, statisticians, and senior scientists for their residents. During these meetings, there were opportunities for the residents to discuss the design of their research project and get feedback from the faculty and fellow residents. They also implemented an Annual Research Day. This was a half-day activity where residents gained indispensable experience on how to present their research work in front of an audience of faculty and fellow residents. They provided a list of faculty that can serve as Research Mentors. They increase their Research project repository by asking their faculty to annually submit a list of research projects or possible research ideas. They made this electronically accessible to residents. They also created a public database that identifies the research status (project identified, institutional review board submitted, data collection, and submission of abstract). Department of Surgery funds covered the expenses for Statistical Support. A Research Director/Coordinator was a dedicated faculty to organize, implement, and maintain the mandatory research program. Lastly, Database mining from national and local organizations and professional societies was done. Improved productivity in research is a result of the time and the action of the resident in conducting research [8].

Study design

To determine the experience of Anesthesiology residents in VSMMC, an analytic observational cross-sectional study design was employed which uses a survey questionnaire. Using this study design, the researcher was able to describe the study population and gather information on the obstacles and assistance needed in researching one point in time.

Study setting

The study was performed at Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center (VSMMC). Which is a century-old tertiary hospital located in the heart of Cebu City, Cebu, Philippines. Specifically near the famous Fuente Circle of Cebu City. This is a tertiary hospital with many residency training as well as fellowship training. All the residency training programs in the hospital are required to submit a hardbound copy of a finished research paper. The VSMMC Research Committee handles all activities regarding research, but it has been until recently that the responsibility has been slowly transferred to the training department.

Population and sampling technique

The study population included all Anesthesia residents who were currently in training. Anesthesia residency is a three-year training. There are currently fifteen residents composed of five first-years, five second-years, and five third-years.

The following are the inclusion criteria:

- All those available at the time the collection is conducted

- Those who are willing to participate in the study

The following are the exclusion criteria:

- Those who are not available at the time of the fielding of the survey and/or those who have decided to not participate in the study

- The questionnaire with missing or incomplete responses from the participants of this investigation.

Definition of terms

Experience in the conduct of research: The practical contact with and observation of facts or events during the conduct of their colleague or their research. This may be their own opinion or a description of a fact.

Anesthesia resident: A medical graduate engaged in specialized 3 year training in the field of Anesthesia under supervision in a hospital. Consisting of first years, second years, and third years.

Data collection procedures: Data was gathered through an online survey which was derived from similar research by Truong and Chan. They first developed the questionnaire, as one of the authors was the Core Faculty in the Residency Program. The questionnaire went through validation, testing, and checking by their faculty physician and Residency Program Director. The questions were then pretested on a senior resident and were then pilot-tested by seven other members of the Residency Program and two members of the Anaesthesiology and Perioperative Science Academic Clinical Program to ensure reliability and clarity. The survey questionnaire is comprised of questions about demographic data, levels of research interest, areas of interest, the obstacles to research, and the potential areas where help can be improved. The online survey was available for a week or until the participants had already finished the questionnaire. The researcher communicated with respondents through different media within the one-week duration of the data collection procedure using the online survey. The online questionnaire was distributed via a link to Google Forms. Upon clicking on the link the respondent was directed to the online survey which a consent form would be on the first page followed by the question proper. If the respondent disagrees, the survey will end. For those who opted to answer through a written questionnaire, it was distributed by the researcher at their most convenient time and place where the respondent could complete the survey form.

Data processing: Microsoft Excel was used for the tabulation of the data as shown in Appendix C. Descriptive Statistics was used to describe the mean, average, or frequency of a data set generated from the questionnaire. The questionnaire consists of three sections: 1) Waiver and introduction; 2) Demographic survey which gathered the following socio-demographic information: gender, age, marital/parental status, current year level, and highest degree; 3) Research profile of the participants: Reasons for taking up research, Level of interest in research, Area of research interest, Previous research activities, Previous research training, Obstacles in doing their research, and Factors to encourage more research involvement. The survey questionnaire is in English form. The research profile was adapted from previous research [1].

Encoding and data cleaning procedure: All demographic and research experience data was summarized as the frequency with the corresponding percentage for categorical data and mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range), whichever is appropriate, for continuous data. Research interest was treated as binary categorical data with categories of interested and not interested. Extremely interested, very interested, and somewhat interested were treated as an interesting category, whereas slightly interested and not at all interested were treated as a not interested category of the outcome variable research interest.

Data analysis plan: Frequency and percentage were used to describe the categorical study variables. Mean and standard deviation were used to summarize the variable Age.

Scope and limitations

Scope: The study determined the Experience of Anesthesiology Residents in conducting Research during Residency Training at Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center. The study involved all Anesthesia residents who were in VSMMC during the time of data collection.

Limitations: The study was limited to Anesthesia residents who are still in residency training in VSMMC and did not include those who discontinued their training before data collection. It covered both facts and opinions perceived by the Anesthesia residents who responded to the survey. The effectiveness of research training was investigated further to explore anesthesia-specific focus areas for residents.

Ethical considerations

No medication, treatment, or medical procedure is involved in this research. There is no conflict of interest in the study. Respondents were asked for their consent to participate in the online survey before they were directed to the self-administered questionnaire. There was no violation of ethical standards in this research study. The research did not ask for or take any financial support from anyone. The researcher solely financed the research and approval from the ethics committee of Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center was secured for the samples to be collected.

A total of 15 respondents answered the online self-administered survey, with a 100% turn-out from the Anesthesia residents. Table 1 shows that respondents’ age ranged from 29 to 34, they have a median age of 30 years old which was close to the mean age of 30.5. With regards to the distribution of gender, there are more males than females but with a slight difference of 67% and 33% respectively. Out of the 15 respondents, 10 of which were male. Among these 15 respondents 73% of which are single. Among the 4 married respondents, only 1 or 7% of them have at least one child. The year level in terms of Anesthesia residency training among respondents is distributed by the third year, the second year, and the first year, as 6, 4, and 5, respectively. All respondents’ highest degrees taken are from the College of Medicine (MD).

| Table 1: Demography of the Respondents. | ||

| Demography of Survey Respondents | Summary | |

| Gender; n (%) | Male | 10 (67%) |

| Female | 5 (33%) | |

| Age; median (mean); range | 30 (30.73); 29-34 | |

| Marital/parental Status; n (%) | Single | 11 (73%) |

| Married without child | 1 (7%) | |

| Married with child/children | 3 (20%) | |

| Current year; n (%) | 1st-year Resident | 6 (40%) |

| 2nd-year Resident | 4 (27%) | |

| 3rd-year Resident | 5 (33%) | |

| Highest degree; n (%) | MD | 15 (100%) |

| MMED | 0 (0%) | |

| PhD | 0 (0%) | |

| MCI | 0 (0%) | |

| MD: Doctor of Medicine; MMED: Master of Medicine; Ph.D.: Doctor of Philosophy; MCI: Master in Clinical Investigation | ||

As demonstrated in Table 2, the majority of respondents believe they complete their study because it is required by the residency program, with 85.7% or 12 of the 15 respondents believing this. While 5 or 35.7% of respondents believe that participating in research may help them advance in their careers. The survey piqued the attention of 3 or 21.7% of the respondents, prompting them to engage in an investigation. Only one respondent (7.1%) believes he was asked to conduct research. Among the respondents, 6 (40%) of which answered the question, Levels of Interest, with somewhat interested. More than half (53.3%) of respondents are either only slightly interested or not interested at all in conducting research. While 1 respondent answered very interested, no one was extremely interested in research. Clinically relevant fields of research were the top choices with 8 (53.3%) of the respondents choosing a research topic. Other research topics the respondents were interested in were Health Services, Education, and Medical technology with 4 (26.7%), 3 (20%), and 2 (13.3%) respondents respectively. When questioned about previous research activities, respondents cited most activities involving data, such as data entry and data collection with 9 (60%) respondents each. Thesis writing, study design, and abstract/poster writing with 7 (46.7%) participants each followed data collection and entry. Three respondents had no previous involvement in research activities. Two-thirds (66.7%) of the respondents have some training in research, which they attended workshops or lectures. While 1 respondent had extensive training in terms of research work. The rest of the respondents had no previous training in research.

| Table 2: Research Profile of all Respondents. | |

| Research Profile | Frequency (%) |

| *Reasons for taking up Research; n (%) | |

| Required for Residency Program | 12 (85.7%) |

| For Career Progression | 5 (35.7%) |

| Interested in the Study | 3 (21.4%) |

| Was asked to do | 1 (7.1%) |

| *Level of Interest in Research | |

| Extremely Interested | 0 (%) |

| Very Interested | 1 (6.7%) |

| Somewhat Interested | 6 (40%) |

| Slightly Interested | 5 (33.3%) |

| Not at all Interested | 3 (20%) |

| *Areas of Research Interest | |

| Clinical | 8 (53.3%) |

| Education | 3 (20%) |

| Health Services | 4 (26.7%) |

| Medical Technology | 2 (13.3%) |

| Basic Science/Translational | 0 (%) |

| No interest | 4 (26.7%) |

| *Previous Research Activities | |

| Data Collection | 9 (60%) |

| Data Entry | 9 (60%) |

| Conference Abstract/Poster Writing | 7 (46.7%) |

| Research Ethic Review Board Application | 4 (26.7%) |

| Data Analysis | 6 (40%) |

| Study Design | 7 (46.7%) |

| Grant Application Drafting and Submission | 2 (13.3%) |

| Thesis Writing | 7 (46.7%) |

| None | 3 (20%) |

| *Previous Research Training | |

| Extensive Training (e.g., Master of Science, Master of Clinical Investigation, PhD) | 1 (6.7%) |

| Some Training (e.g., attended workshops, lectures, able to perform some research activities with confidence) | 10 (66.7%) |

| No Training | 4 (26.7%) |

| *multiple response item | |

The obstacles that respondents feel they encounter in doing research were asked. Respondents cited that the lack of time to balance clinical and research responsibilities is the most common obstacle encountered by 13 (86.7%) respondents. Researchers feel they have inadequate research skills as it was the top 2 answer respondents selected with 73.3%. Lack of time in balancing responsibilities between family and work was among the most common answer by the respondents with 60% or 9 respondents. Personal motivations like lack of interest and lack of interest were selected by 46.7% of respondents, followed by lack of mentorship with 33.3%. The rest had less than 5 (33.3%) respondents. Additional help was cited by respondents as well, guidance from a mentor, biostatistician, institutional/departmental support, and admin support with at least 20% or 3-4 of the respondents. Finally, a venue for research activities was also identified like infrastructure, access to journals, as well as activities to attend or present a research presentation.

Table 3 shows the frequency of the obstacles mentioned by the participants. Table 4 shows the frequency of the factors to encourage more research involvement. The factors that the respondents feel may encourage them to increase involvement in research work. The top 2 answers by the respondents were related to protected time for research with unsupervised and supervised time with 93.3% and 86.7% of respondents feeling that more protected time for research, and attending workshops related to research might give them time and interest to be involved in research activities.

| Table 3: Obstacles in doing Research. | |

| Obstacles in doing Research | Frequency (%) |

| Lack of time (Balance clinical and research responsibilities) | 13 (86.7%) |

| Lack of Mentorship | 5 (33.3%) |

| Lack of time (Balance Family and work Responsibilities) | 9 (60%) |

| Inadequate Research Skills (eg. How to design a study, Statistical analysis) | 11 (73.3%) |

| Lack of Institutional or departmental support (eg Paid time off for research) | 4 (26.7%) |

| Lack of research admin support | 2 (13.3%) |

| Lack of access to biostatistician | 3 (20%) |

| Lack of access to research tools/software such as biostatistics software, referencing software | 3 (20%) |

| Lack of funding | 2 (13.3%) |

| Lack of motivation | 7 (46.7%) |

| Lack of access to scientific journals | 1 (6.7%) |

| Lack of personal interest | 7 (46.7%) |

| Lack of access to lab/research infrastructure | 1 (6.7%) |

| Lack of opportunity to present research work | 1 (6.7%) |

| Table 4: Factors to encourage more research involvement. | |

| Factors to encourage more research involvement | Frequency (%) |

| Provide supervised protected time for research work (e.g. regular meet-ups with a research mentor, lab time) | 13 (86.7%) |

| Provide department research manpower support (research assistant/research executive/clinical trial coordinator) | 6 (40%) |

| Mentorship with topic expertise | 9 (60%) |

| Provide un-supervised protected time for research | 6 (40%) |

| Provide un-supervised protected time for lectures/workshops | 14 (93.3%) |

| Provide more opportunities to attend overseas conferences | 3 (20%) |

| Make self-learning research skill training materials available | 3 (20%) |

| Provide financial incentives | 7 (46.7%) |

| Career advancement reward | 7 (46.7%) |

The third most cited answer was the availability of a mentor with topic expertise at 60%. While financial funding and career advancement incentives with 46.7% were the fourth and fifth most common answers. Providing manpower support and time to complete research was also noted by 40% of the respondents. While opportunities to attend overseas conferences and the availability of self-learning skill training materials were cited by 20% of the respondents.

This study conducted in Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center found that Anesthesiology Residents expressed some interest in performing research. The study found that the most prevalent barriers to research engagement during residency were a lack of time and a lack of mentoring, which is consistent with earlier studies [1,2]. These findings coincide with the top 2 possible solutions that may encourage involvement in research activities both entail protected time to focus on research may it be supervised or unsupervised. In residency training there are many competing priorities for residents’ and consultants’ time, thus this barrier can only be modifiable to a certain degree. Preceptors and residents may be provided with dedicated and strategically placed blocks of time during which the demands of rotations are put on hold to focus on conducting researchrelated activities. Program and department administration may consider creative and innovative ways to provide dedicated and strategically placed blocks of time during which the demands of rotations are put on hold to focus on conducting research-related activities. Some residency programs have a “research month” in December, while others have numerous research weeks or days spread out throughout their residency. Additionally, aligning less stressful rotations with project objectives or dedicating days during a rotation to research may boost resident confidence, morale, and productivity. Finally, departmental management is encouraged to assess mentor staffing-to-workload numbers regularly to see if dedicated, nondiscretionary time for doing research or guiding resident research during planned work shifts may be allowed [2,4]. Offering protected time may be a viable strategy. However, rather than giving residents unsupervised protected time to explore research work, it may be more practical to give protected time for a research syllabus.

Residents should be encouraged to approach their research mentor, program director, or department head if they require such guidance. This will allow for adequate planning and resource allocation. Almost two-thirds of survey respondents noted a lack of devoted research mentorship. To address this, a better mentor-mentee matching scheme, co-mentoring, and an incentive program for faculty engagement should be investigated. Compensation for teachers agreeing to be mentors has been reported to include conference time and monetary incentives. Effective research mentorship may increase residents’ desire to participate in research. A study done in Canada showed that increased resident publications were strongly linked to active program director support, research participation, and publication. Residents can identify with a researcher and learn from him or her since research mentors are available. The message that research is valued inside the program is conveyed through support and role modeling [9].

It is remarkable how residents in the past were able to do their research despite a shortage of time; the study revealed that Anesthesia residents focus on their research since it’s mandated by their training program. Extrinsic reasons, such as a need, should not be the driving force for research. A study by Chan suggested that extrinsic incentives are not significantly associated with research participation. They also discovered that residents’ perception of the intrinsic value of research had a significant impact on research engagement; hence, the lower-than-expected participation rate might be a signal of residents’ lack of conviction in the inherent worth of research [9]. Very few residents are enthusiastic about research, according to this survey, while the majority are either uninterested or only somewhat interested. Residents should be inspired and taught about the importance of research and how it may help them enhance their clinical skills.

A study of Canadian anesthesiology residents found the same thing, specifically, a lack of protected research time, interest, and a research-related curricular shortfall that precluded them from participating. The same study showed that many Anesthesia residents in Canada believe that mastering the clinical elements of their specialty should take up the majority of their time. Although Canadian anesthesiology residents acknowledge that free time is allocated for research, residents said that family and other obligations were significant hurdles to completing a research assignment. This could be due to lifestyle factors similar to those of radiology residents [10], who are less inclined to give up personal time for research that is seen as an afterthought rather than a necessary element of the curriculum [11]. In considering for structured research curriculum in the residency program, dedicated time must also be paired with activities that will entice residents to complete their research output.

Lack of skill in statistical analysis, lack of research experience, and lack of training in research methodology were barriers to participating in research activities during residency, this was consistent with the outcome in previous research [2,12]. Most of the residents had experienced different types of research-related activities and had some research training but most of them felt they did not have enough experience or skills in research. It is also highly likely that incoming residents have varying knowledge and experience in research. Existing residency programs frequently undervalue basic research abilities and fail to meet the unique learning demands of residents, whose prior exposure to research principles varies greatly.

In one recent study, A supplemental educational experience was created to fill educational gaps in a family medicine residency curriculum, including systematic exploration and interpretation of medical literature, the development and exploration of clinically relevant questions, and the development of residents’ written communication skills. A self-directed online research curriculum was devised and implemented in a family medicine residency, and residents rated it favorably in terms of satisfying curriculum objectives and satisfaction. This shows that an online, self-directed curriculum could be a viable and effective component of intellectual activity residency training [13].

The existence of research-related optional courses in the Anesthesiology program may encourage seniors to develop an academic interest, boost resident research publications, and explore research as a career progression option. Many residents have different challenges concerning the scientific approach, like a small sample size. If a certain research project has a small sample size available for the study, partnerships with other institutions may increase the study sample. It is also possible to expand the number of years in the collection of data, but the number of years in residency training may limit this as well [4]. The syllabus might be tailored to give formal instruction or technical assistance in research techniques, as well as possibilities for individualized and guided research experiences. This may be especially important in our local context, given that the majority of residents questioned felt that a lack of statistical analytic skills, research experience, and research technique training were impediments to participating in research activities during residency.

Graduates of Canadian programs with formal research curricula were more likely to say their residency research project was a beneficial learning experience. Participation in a research project should not be an obligation of the curriculum; rather, it should be the climax of a broad educational experience [10,14].

A very recent study compared the resident involvement in research activity before and after the implementation of a culture of research in the program, revealing that implementing a structured roadmap for the research activity is linked to higher resident research activity production and the establishment of scholarly culture in a program. The study noted a double of research publications by those who were exposed to the structured roadmap [15].

Recommendations

Residency training allows for the focused development of advanced research abilities. This is a significant step in many residents’ aspirations, and it also helps the profession by publishing innovative research and increasing the number of qualified researchers. Programs can strengthen their research curriculum, improve the experience, and increase output by taking into account several identified concepts, such as proactively identifying and addressing research-related barriers specific to their practice site and taking a structured and multifaceted approach to teaching research concepts and their practical application. The investigator believes that these actions will increase overall happiness and success for residents, program directors, advisers, and partners alike. Improving the quality of evidence in the anesthesiology literature by addressing these barriers and improving our present research landscape. This enables us to develop improved procedures and standards of care that not only improve our efficiency and efficacy as anesthesiologists but also help us achieve the best possible outcomes for the patients we serve.

The motivation for conducting research during anesthesia residency is primarily driven by the necessity to complete residency training. Many residents recognize the value of research, not only as an academic requirement but also as a means to enhance their clinical expertise, improve patient outcomes, and contribute to the growing body of knowledge in their field. However, despite the recognition of these benefits, several barriers hinder their ability to engage in research activities.

The most significant obstacles reported by Anesthesia residents are a lack of time and inadequate access to research mentors. Time constraints are especially pressing during residency, where clinical duties, patient care responsibilities, and educational requirements often take precedence over research endeavors. The limited availability of research mentors, who can guide residents through the complexities of research design, methodology, and data analysis, further compounds this challenge. Without mentorship, residents may struggle with structuring meaningful research projects, securing funding, or navigating the intricate regulatory requirements associated with conducting studies.

These barriers are not insurmountable, and addressing them could significantly improve the research environment for residents. Solutions might include adjusting the residency schedule to allow dedicated research time or fostering a more structured and accessible mentorship network. By encouraging collaboration with experienced researchers and facilitating opportunities for residents to engage with ongoing projects, residency programs can provide critical support to cultivate a culture of research within anesthesia training.

The identification of these challenges presents an opportunity for residency programs to actively intervene and modify their structures to better support resident research. By offering practical solutions and creating a more research-friendly environment, programs can ensure that residents are equipped not only with clinical expertise but also with the research skills necessary to contribute meaningfully to the evolving field of anesthesiology. Furthermore, addressing these barriers will likely lead to increased research participation, fostering a generation of anesthesiologists who are better prepared to address the complex and dynamic healthcare challenges of the future primary motivator to conduct research is to complete the residency training.

The top barriers to research are lack of time and inadequate access to research mentors. These barriers can be addressed to optimize the current research environment for residents. Anesthesia residents identified several critical aspects that they believe are obstacles to research. These findings can be used by programs to overcome hurdles and increase the inclusion of research into residency training.

- V.S.M.M. Center. Statement of Quality Policy for QMS. 2020.

- Ha JJ, Truong TT. Interest and experience of anesthesiology residents in doing research during residency training. Indian J Anaesth. 2019;49(4):257-262.

- Personett HA, Hammond DA, Frazee EN, Skrupky LP, Johnson TJ, Schramm GE. Road Map for Research Training in the Residency Learning Experience. J Pharm Pract. 2018;31(5):489-496. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/0897190017727382

- Fournier I, Stephenson K, Fakhry N, Jia H, Sampathkumar R, Lechien JR, et al. Barriers to research among residents in Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery around the world. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2019;136(3):S3-S7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anorl.2018.06.006

- Vinci RJ, Bauchner H, Finkelstein J, Newby PK, Muret-Wagstaff S, Lovejoy FH. Research during pediatric residency training: Outcome of a senior resident block rotation. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4):1126-1134. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-3700

- Nasr VG, Ahmed I, Bonney I, Schumann R. Research and Scholarly Activity in US Anesthesiology Residencies: A Survey of Program Directors and Residents. ISRN Anesthesiol. 2012;2012:1-9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5402/2012/652409

- Devereaux PJ, Beattie WS, Choi PT, Badner NH, Guyatt GH, Villar JC, et al. How strong is the evidence for the use of perioperative beta blockers in non-cardiac surgery? Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2005;331(7512):313-321. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38503.623646.8F

- Papasavas P, Filippa D, Reilly P, Chandawarkar R, Kirton O. Effect of a mandatory research requirement on categorical resident academic productivity in a university-based general surgery residency. J Surg Educ. 2013;70(6):715-719. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2013.09.003

- Hames K, Patlas M, Duszak R. Barriers to Resident Research in Radiology: A Canadian Perspective. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2018;69(3):260-265. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carj.2018.03.006

- Silcox LC, Ashbury TL, VanDenKerkhof EG, Milne B. Residents' and program directors' attitudes toward research during anesthesiology training: A Canadian perspective. Anesth Analg. 2006;102(3):859-864. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/anesthesia-analgesia/fulltext/2006/03000/residents__and_program_directors__attitudes_toward.30.aspx

- Chan JY, Narasimhalu K, Goh O, Xin X, Wong TY, Thumboo J. Resident research: Why some do and others don’t. Singapore Med J. 2017;58(4):212-217. Available from: https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2016059

- Williams AA, Ntiri SO. An Online, Self-Directed Curriculum of Core Research Concepts and Skills. MedEdPORTAL J Teach Learn Resour. 2018;14:10732. Available from: https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10732

- Waheed A, Nasir M, Azhar E. Development of a Culture of Scholarship: The Impact of a Structured Roadmap for Scholarly Activity in Family Medicine Residency Program. Cureus. 2020;12(3):1-7. Available from: https://assets.cureus.com/uploads/original_article/pdf/28109/1612429805-1612429796-20210204-18203-1ezm2li.pdf

- Crawford P, Seehusen D. Scholarly activity in family medicine residency Programs: A National Survey. Fam Med. 2011;43(5):311-317. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/51112240_Scholarly_Activity_in_Family_Medicine_Residency_Programs_A_National_Survey

- The Canadian Plastic Surgery Research Collaborative (CPSRC). Barriers and Attitudes to Research Among Residents in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: A National Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(6):1094-1104. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.04.004

- Omi FR, Barua L, Banik PC, Faruque M. A protocol to assess the risk of dementia among patients with coronary artery diseases using CAIDE score. F1000Research. 2021;9:1256. Available from: https://f1000research.com/articles/9-1256